Six Months is a long time in Cricket

It is said that a week is a long time in politics. Similarly, six months is a long time in cricket as seen by the rise of the West Indies in 1976. Between 1976 and 1992, the West Indies were the most dominant team in international cricket with an amazing mix of world class batsmen and fearsome fast bowlers. Nearly fifty years later this walk down nostalgia lane has some interesting insights about how players are selected, cricket is played, and how teams perform.

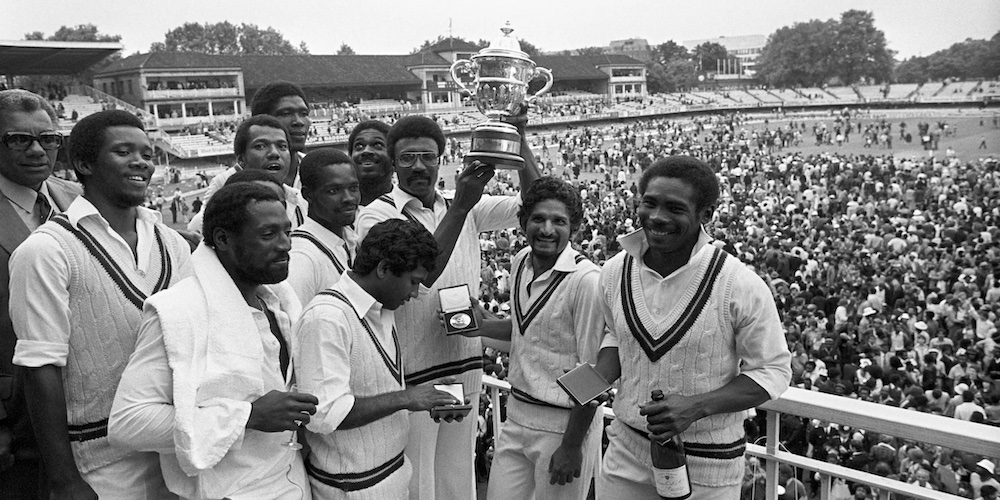

In 1975, Clive Lloyd’s team won the inaugural World Cup defeating Australia by 17 runs in the final. The West Indies batting line up was Roy Fredericks, Gordon Greenidge, Rohan Kanhai, Alvin Kallicharran, Clive Lloyd, Viv Richards, Bernard Julien, Deryck Murray, and Keith Boyce. Its bowlers were Andy Roberts, Boyce, Julien, Vanburn Holder, and Clive Lloyd who incidentally had the best bowling figures of 12 overs for 38 runs.

Buoyed by the win at Lords, the West Indies traveled to Australia for what was then dubbed the unofficial world test championship. The Windies added one formidable batsman to the batting order as Lawrence Rowe came into the side for the retired Kanhai. In the bowling line up, Lance Gibbs, as the premier spinner in the West Indies, was brought in for one last hurrah.

Writers tend to call the West Indians a young team but they were far from that as they had veterans in Lloyd, Fredericks, Gibbs, Kallicharran, Boyce, Holder, and Murray which created a spine of experience that could guide newcomers like Greenidge, Roberts, and Richards.

The Australians were just as good because their team had the Chappell brothers, Doug Walters and Ian Redpath, and a first rate keeper batsman in Rod Marsh. But the bowling was in a class of itself. Dennis Lillie had come back from a back injury and with 21 tests under his belt was a veteran in his prime. In tandem was the ferociously fast Jeff Thomsom who had played only ten tests but in those had terrified the English batsmen. People also forget the able support provided by the fast-medium bowlers Gary Gilmour and Max Walker. Both were to bowl superbly in the series and Gilmour ended up with 21 wickets.

While the West Indians were strong on paper, there was a fragility and lack of discipline to the side. Against the bowling of Lillie and Thomson, the West Indians decided that rather than waiting around to be bowled by the hostility and accuracy of Lillie and Thomson, the best policy was to hook or hit out. In part this worked because the three veterans — Lloyd, Fredericks, and Kallicharran — all got over 400 runs in the series and in the fifth and sixth tests a certain Viv Richards was pressed as an opener and scored 101, 50, and 98 (he also scored 400 odd runs). But the wild hooking led to players throwing away their wickets rather than building innings.

The other problem was that the bowling of Lillie and Thomson had begun to bite as players were intimidated by the pace and were getting hit. Greenidge, belying his later reputation, failed against extreme pace and was replaced for the second test. The story goes that Lloyd did not favor the dedicated opener Leonard Baichan and instead wanted a makeshift opener to partner Roy Fredericks at Perth. The problem was no one wanted the job.

Lawrence Rowe who had opened for the West Indies and was considered one of the best players in the world went and sat in the toilet for a long time while Lloyd looked futilely for a volunteer. Finally, the 40 year old Lance Gibbs who had a batting average of 6.97 volunteered. Shamed by the batting rabbit’s offer, Bernard Julien opened with Fredericks and the latter smashed one of the best centuries ever in test cricket. He hit 169 in 145 balls reaching his century in 71 balls. This was with no field restrictions! The West Indies won convincingly with Roberts taking seven Australian wickets in the second innings. What followed was a debacle as Australia won the next four tests.

The problem was that the Australians were a seasoned unit who had experience, individual talent, and had played together as a team. Additionally, if one accepts Michael Holding’s version, the Australian umpires were favoring the home side (something that was a major problem before neutral umpires were introduced as seen by the fact that the first time Javed Miandad was given out LBW in Pakistan was after the introduction of neutral umpires).

Lloyd, himself, had yet to become the formidable captain he later became and allowed the team spirit to break for as the team’s performance deteriorated a lot of finger pointing and accusations followed. Additionally, the West Indies selectors had engaged in their usual politics in selection and not looked for the best players for the particular conditions in Australia. By then, the world knew about the speed and lethality of Lillie and Thomson because of two test series against England but the selectors sent a group of medium-fast to fast-medium bowlers to support the genuinely quick Andy Roberts and the budding talent of Michael Holding. Boyce and Julien, as seamers, could bowl effectively in England but in Australia they were less effective (Julien, before he got injured, was able to take 11 wickets in 3 tests for an average of 27.55).

The West Indian selectors should have included Colin Croft in the team because, by then, he had been playing domestic cricket in the West Indies for three years and his speed must have been noticed. A trio of Roberts, Holding, and Croft would have put greater pressure on the Aussies and kept the games closer.

Equally telling was the lack of a player or players who could anchor the innings. Instead the team was full of stroke players who were intent on hooking the short-pitched bowling of Lillie and Thomson. The West Indians failed to adapt to the fact that what went for a six in Port of Spain or Kingston was going to be caught in the deep on the larger Australian grounds.

By the sixth test the West Indies had been convincingly beaten but there were glimmers of hope. Viv Richards had shown that he was an outstanding batsman and that his performance in the earlier series against India was not a flash in the pan. Roy Fredericks had developed into a fine opener (Thomson was to say that the only players who could get their feet into position in time to play him were Fredericks and Greg Chappell) and Michael Holding looked like a world class pace bowler.

The Australia series ended on the Fourth of February 1976 and a shell-shocked West Indies returned to their islands. Within a month they were playing another series this time against India. The first test was in Barbados and David Holford, who by then was an occasional selection for the West Indies, spun the Indians out cheaply in the first innings. In response, Richards and Lloyd hit centuries and the West Indians won the game. In the next test at Port of Spain, Richards hit another century but Gavaskar replied in kind and the game petered out in a draw. What came next, however, was unexpected and had long-term consequences for the West Indies.

The third test was also at Port of Spain and Richards set the tone with his third consecutive century. India’s reply was modest and in the second innings the West Indians got another 271 runs and set India a target of 403 — something that had only been done once before in test cricket.

Lloyd did not have Roberts but Holding was in the team along with three spinners — Albert Padmore, Imtiaz Ali, and Raphik Jumadeen — which, because the pitch was turning, should have given the West Indians the fire power to bowl India out. But the Windies spinners were at best Ranji Trophy level players and the Indians had accomplished players of spin in Gavaskar and Vishwanath who took India to victory.

Lloyd was reportedly furious and told his spinners that he had given them a huge total which they could not defend so from then onwards he was going to depend on pace. For the next test the West Indians had Holding and another very fast bowler in Wayne Daniel and on a pitch that was fast and had an uneven bounce they engaged in a barrage of short pitched deliveries against India. In the second innings, with half the team injured, Bedi declared the innings at 97/5. The West Indies knocked off the few runs needed for victory.

Commentators in the West Indies, most notably the arrogant and stupid Tony Cozier, accused the Indians of cowardice but on a poor pitch and with umpires who were unwilling to rein in the barrage of bumpers, Bedi took the wise decision. Many years later a sub-standard pitch at the same venue saw the test being cancelled on the first morning after several English batsmen had been badly hit. Of course, no one in the West Indies called the English cowards. Too many West Indians played in the English country championship or in the Yorkshire and Lancashire leagues.

Today, no West Indian would be stupid enough to call an Indian team cowards since that would be the end of their career in the IPL and the players of today will not take that kind of verbal abuse from anybody. Sadly, it was a different India with different values.

Lloyd having found his formula took Roberts, Holding, Daniel, and Holder to England for the third test series of the year which began on June 3 against England. Roberts bowled brilliantly in the series to take 28 wickets and in the last test at the Oval, on a slow wicket, Holding bowled with sustained speed and hostility to take 14 wickets for 149 in the test. He too ended up with 28 wickets. But if the bowling was a revelation, the batting did not disappoint either.

Viv Richards, who only played four of the five tests, got 829 runs with two double centuries. Greenidge got 592 while Fredericks got 517. The West Indies had found their bowlers and the batsman who would define their playing style for a generation. A transformation that took place in five months.

What were the lessons from the rise of the West Indies? First, selectors tend to cling on to players long past their prime. As a consequence, they overlook promising young talent. If Croft and Daniel had gone to Australia would it perhaps have been different?

Secondly, learning from their mistakes, the West Indies produced a stable of fast bowlers who dominated the game for the next fifteen years. In 1977, Colin Croft and Joel Garner got their debuts. A year later, Sylvester Clarke made his debut. The West Indies had a surplus of fast bowling riches.

Thirdly, the West Indians, as they matured became more disciplined batsmen and the wild hitting of the Australia series gave way to a systematic effort to build each innings.

To sum up, six months is a long time in cricket.

(Amit Gupta is a Senior Fellow of the National Institute of Deterrence Studies in the USA)